“It is highly unlikely that functioning farming enterprises will be confiscated… Farm invasions are extremely rare in South Africa. I do not recall one in the last couple of years.”

Listening to Max du Preez, one of South Africa’s most-respected political commentators talking about land expropriation to an audience of 900 members of the industry at the Nedbank Vinpro Information Day in January inevitably made me recall that other gathering in the same country, almost precisely 31 years earlier. On that occasion – as I reported for Wine & Spirit magazine – a group of prominent wine producers had sat on their hands after listening to John Platter suggesting that the black and coloured community should be allowed to own vineyards and play a fuller part in industry. Back then, the idea that a democratically-elected black administration might ever be in a position to discuss land ownership was a long way from anyone’s horizon.

All of these encounters – and the side trip I took to Zimbabwe where I learned that President Mugabe had far fewer scruples when it came to drinking South African wine than my liberal London friends – made me glad I’d made the journey. And almost certainly made me keener to return repeatedly over the following post-apartheid years.

Over that time, I watched how the South African ugly duckling was perceived to have turned into a swan. Those words were not written casually. If some critics were to be believed, the 1994 election instantly cleansed the Cape and its producers of their pariah status and gave their wines a free pass to the vinous premiership.

But of course it wasn’t that simple. Just as post-Soviet Eastern Europe continued to be run by the same people, some of the pig-headed Afrikaner bastards I met in 1988 were still prominent in the industry a decade later. And few of the wines deserved to be taken as seriously as they were in the 1990s. The vineyards were riddled with leaf roll virus that prevented the grapes from ripening; brettanomyces was rife; there was far too much reverance for – and reliance on – Pinotage; and too few winemakers had travelled and tasted sufficiently widely to see how the world had moved on during the years of isolation.

In 1995, I was a judge at the first – and only – SAA Shield tasting in Cape Town, at which South Africa and Australia each fielded 100 wines across 11 categories. It was a walkover for the Aussies who won eight of them, leaving the home team to pick up the trophies for ‘open dry white’, ‘dessert’ and – surprisingly – Riesling. The overall result, however, came as no shock; it was precisely in line with what I saw every year at the IWC.

From the outside, it felt as though everything really began to change with the Millennium. In the first decade of this century, I chaired three years of the Swiss International competition in Constantia and the same number of Tri-Nations contests in Sydney – and watched the quality of South African wine blossom, as the vineyards were cleaned up (though not entirely) and a younger generation take the reins.

Which brings me to the present day when events like the Nederburg auction at which I spoke in 2017 and Cape Wine are full of really impressive examples of a broad range of styles.

But it would be dangerous to be dazzled by those successes. Behind the scenes, there are still plenty of challenges. South Africa may have rejoined the free world, but the drive from Cape Town to the winelands takes you past the same shanty townships I saw in 1988. According to the World Bank, in 2017, 18.6% – nearly one in five – of the population was still living on $1.90 or less per day.

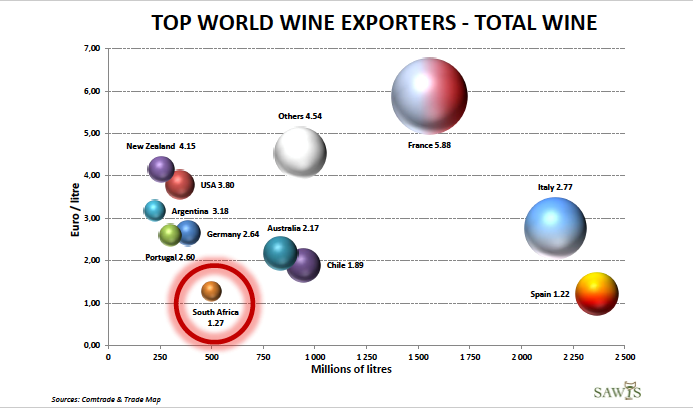

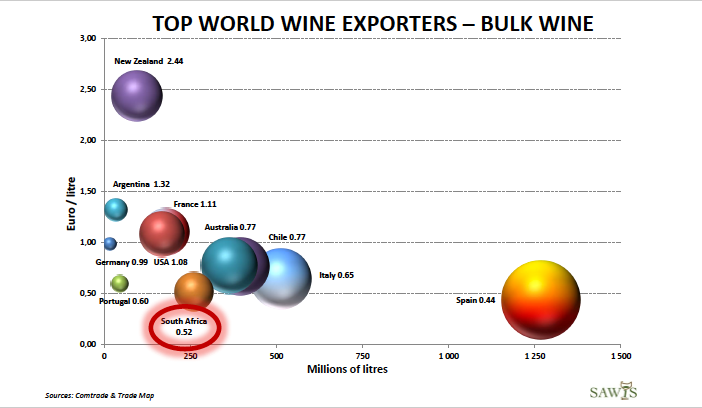

In 1988, half the annual wine harvest went straight off to be distilled. Today, it’s sold off cheaply in bulk. As other speakers at the Nedbank Vinpro bluntly pointed out, South Africa competes with Spain to be the producer of the cheapest wine on the planet. When French shoppers pick up bottles of strawberry-flavoured wine, the fermented grape juice component probably came from the Cape. To put this into round figures, as Christo Conradie of Vinpro explained,”More than 80% of SA wine producers are farming below a sustainable net farm income of R30 000 per hectare.”

The recent droughts which have dramatically cut production have helped to raise prices and provide what Coneradie called the ‘silver lining’, but the industry still struggles to keep up with South Africa’s 7% inflation rate. And water remains a huge concern. As the manager of Vinpro’s viticulture consultation services, Francois Viljoen, said,“Last year was the most challenging season ever. Some vineyards were abandoned to save water or to save other vineyards.”

Winemaking skills have improved hugely, but as Mike Ratcliffe of Vilafonte told the same conference in 2018, a lot more effort has to go into training vineyard workers. Ratcliffe, who recently sold his family’s Warwick Estate for what was reckoned to be a very high price, also believes that the South African industry needs to have more self confidence – and greater readiness to charge more for its better wines.

Another issue that was raised at the 2019 Nedbank Vinpro event was the need for more investment both from within South Africa and overseas. Vineyard acreage is shrinking every year because of a lack of replanting. Which inevitably brings us back to the threat of expropriation.

In December, 2018, the ANC conference, pandered to the former leader of its Youth League, Julius Malema, by tabling a draft bill that included expropriation of land without compensation as an elements of land reform. ‘Interested parties’ have until February 22 to comment on the bill, and at some point this year there will be a general election in which the subject is bound to be raised.

The outcome of that vote will be hugely important to the wine industry. If the current president and ANC leader Cyril Ramaphosa were to get over 60% of the votes, local observers predict an outbreak of ‘Ramaphoria’, followed by an influx of foreign investment. If he were to get less than 50%, he’d have to go into coalition with Malema’s EFF party and would risk being ousted as leader – a scenario that would naturally concern current landowners and potential investors.

Neither result is seen as likely – but nor was Donald Trump’s victory or Brexit. And some potentially bitter land reform pills may in any case have to be swallowed. Twenty-four years after Nelson Mandela was elected, in 2018 a World Bank report entitled ‘An Incomplete Transition’ found that, largely due to poor education, South Africa’s inequality in both income and wealth is the “highest observed in World Bank data”. The financial institution also addressed “skewed distribution of land and productive assets and weak property rights”. In the former homelands, agricultural land is communal; township residents don’t have tenure of their homes and the “unequal desibution of wealth puts pressure on property security for investors” especially for “mining and agriculture”. A category that, as readers of this post will appreciate, includes viticulture.

I wonder how many of the overseas visitors to Cape Wine this year will know or care to know about any of this. I’m sure there will be some readers who have got to the end of this piece saying something along the lines of “less politics and more wine please”. My only answer to them is to respectfully suggest that they look elsewhere for their vinous enlightenment. I am not naturally a politically engaged person, but Apartheid, Brexit and Trump are three subjects that have made me get out of my seat, and I make no apology for doing so.

In any case, politics are woven tightly into the history of wine. It was, after all, politics that drove some 24,000 Irish men, women and children to France in the 1690s after the Battle of the Boyne – and directly led to the creation of Bordeaux chateaux such as Lynch-Bages, Léoville-Barton and Pichon-Lalande. And of course it’s politics – and the owner’s dislike of the EU – that mean that tonight, as I write this, customers of 900 Wetherspoons pubs across the UK will not have the opportunity to drink a wine or beer from Europe. Which might, of course, be good news for some producers in the Cape…