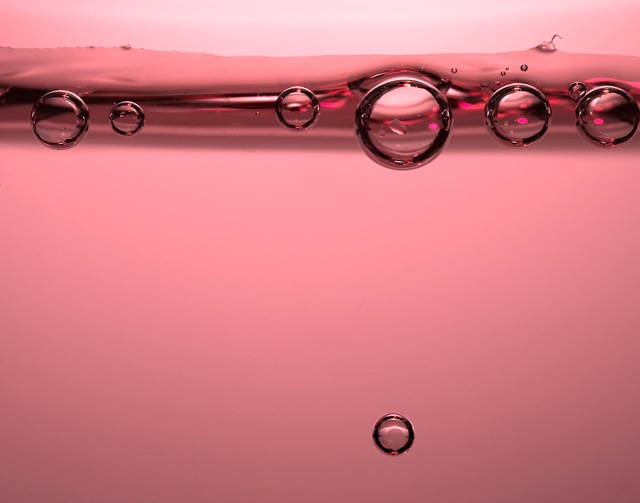

Why is it that some sparkling wines glide like fluffy meringues whilst others seem to fizz and froth like an angry jacuzzi? The route to the finest bubbles is one whose intricacy may make you pause for thought next time you pop a cork.

“Sparkling Wine Bubble Researcher” may sound like something you’d see printed on a joke T-shirt, but consider this; all over the world there are glasses being poured in front of eagle-eyed customers, ready to send anything back that fails to sparkle. Not only do sparkling wine producers need to deploy all their technical skills to create the finest bubbles possible, they then want to know how to guarantee their wine displays – and keeps – its effervescence. Can bubble science help us solve the mysteries of the mousse?

A Bubble Science Primer

Almost all sparkling wine undergoes a second fermentation in a closed environment, trapping carbon dioxide (CO2) in the wine. This could be the bottle itself (for Champagne or any ‘traditional method’ sparkling wine) or a tank (for Prosecco or any ‘tank method’ wine). When a glass of sparkling wine is poured, tiny fibres in the glass form ‘bubble nurseries’ where this CO2 is able to make its escape. Without these nurseries, no bubbles would appear at all. Differences between glasses will mean that a visual inspection of the rising ‘bead’ of bubbles may not tell you how bubbly the wine really feels to drink.

The real action happens on our palates, where the dissolved CO2 finds plenty of sites to raise its offspring. Not only do we physically feel the bubbles, but recent research has shown that we actually taste them: the CO2 reacts with moisture in our mouth (via a fantastically-effective enzyme called carboanhydrase found in our tongue) to form carbonic acid, the effect of which is crucial to the tingling sensation we find in any fizzy drink.

We’re hoping for something a bit more sophisticated than a can of soda, though; what are the qualities of the finest sparkling wine mousses? I asked Champagne expert and author of Christie’s World Encyclopedia of Champagne and Sparkling Wine, Tom Stevenson:

“ A silkiness of mousse is ideal and this is essentially achieved by a combination of bubble size (the smaller the silkier) and pressure (the lower the silkier)…textural silkiness enhances the finesse of a sparkling wine, but it is not a magic wand – the finesse has to be there in the first place.”

Dr. Belinda Kemp, an oenologist specialising in sparkling wine based at Canada’s Brock University, takes things one step further:

“It is a bit of a minefield. I would say it is as much to do with stability, integration and balance as it is size and pressure. It comes down to temperature during storage, the type of storage and ageing time. You hear a lot of people say Charmat method wines have bigger bubbles – well yes, it’s a completely different method after all. But as we start to see longer lees-aged Proseccos we can’t say that will categorically be the case. Proseccos are lower-pressure – but they don’t necessarily have smaller bubbles!”

One thing is clear – we know a great mousse when we taste one, but for now the sensory science is still fermenting. There is one area where science is starting to explain what generations of winemakers in Champagne have observed: that time and temperature are crucial. Why is it that the finest bubbles always seem to emanate from the cool, unhurried cellars of top ‘Traditional Method’ producers?

Time, Temperature and Tradition

Certain kinds of proteins found in sparkling wine are both hydrophobic (water-hating) on one side and hydrophilic (water-loving) on the other – they can’t make up their minds whether they want to be inside the wine or outside it, so they end up stuck in the skin of bubble, reinforcing it. The art of the finest mousse relies on coaxing yeast into producing these kinds of proteins both whilst merrily fermenting away and, crucially, after they have expired in the bottle and formed the lees which the wine ages on.

If the wine is slightly too warm, or doesn’t spend enough time on lees, then the yeast won’t play ball, whether dead or alive. If, on the other hand, the wine is kept at somewhere near 12°C and spends at least 18 months on lees (or much longer in the case of most vintage and prestige cuvée wines), then we can start hoping for that elusive, slow-releasing stream of bulles fines that comes with ‘supersaturated’ CO2 and fine, slow-releasing bubbles.

Perlage in Peril

There are plenty of opportunities for things to go wrong. Aggressive bubbles are a frequent complaint, often found in youthful wines that contain too much CO2. To avoid this, sparkling wine producers sometimes reduce the pressure of their wines by giving the yeast less sugar to feed on, reducing the amount of CO2 (this is part of the style of Crémant wines, although Champagnes and sparkling wines the world over are increasingly refining their approaches). The wrong yeast strains, too much yeast (or poorly-managed nutrition), warm temperatures, insufficient ageing time…all potential culprits for coarse or quickly-dissipating mousses.

In the vineyard, the main enemy of bubbles is the fungus botrytis cinerea, which arrives in damp and humid vintages such as that experienced by parts of Champagne in 2011 and 2017. Not only can rot alter the balance of proteins in the wine, impairing its ability to foam, but treatments aimed at dealing with it in the winery can make matters worse. Bubble scientist Gérard Liger-Belair believes that the “trend toward increasing humidity and rising air temperature” in Champagne could present future hurdles for Champagne’s bubble-conscious winemakers, precisely because of the risk of rot.

Cost-cutting can spell trouble, too: wines from grapes that have been pressed too hard in order to extract more juice can end up rich in bitter-tasting phenolic compounds that inhibit bubble stability. Even with good pressing, Belinda Kemp still ventures that there can be a “massive difference” between Pinot Noir and Chardonnay from the same vineyard, with Chardonnay having the potential for a finer mousse thanks to lower extraction of phenolics. Another reason, perhaps, why blanc de blancs styles often seem to capture that creamy lightness?

Most top sparkling wine producers follow the Champenois in strictly regulating how hard grapes can be pressed. Even so, cheaper Champagnes and sparkling wines are liable to use more tailles – the ‘tail end’ of the pressing – meaning the texture could veer closer towards wooly-jumperthansilk handkerchief.

The Final Hurdle

When it comes to serving a sparkling wine, detergent residue is a notorious buzzkill, smothering bubble nurseries and preventing nucleation. Not only do we miss out on the visual side of the bubbles, but also the wine’s aroma; the complex circulation patterns that bubble streams create continuously ‘renew’ the surface, enabling volatile aroma compounds to escape.

Pop that cork, pour a glass (gently, at a 45 degree angle)…and wait. Sensory research from UC Davis in California has shown that sparkling wines that rest five minutes in the glass not only show more of their individual character, but also display improvements in bubble texture. This is attributed to the wine having worked through its initial rush of CO2 dissipation upon opening to more of a ‘plateau’.

So next time you open a bottle for guests, make sure you prepare your five-minute patter – a small speech, a few jokes – or perhaps even a brief explanation of bubble dynamics.

Photo by Michael Dziedzic on Unsplash