“You’re joking,” said María Hontoria, the oenologist from the governing Cabildo de Tenerife. “I thought everyone from the UK had been here.” Her surprise was justified. Nearly six million tourists visit each year and more than a third are Brits. Tenerife is package tour central, served by dozens of airlines holiday makers to resorts like the Playa de los Américas, but it’s also much more than that: a beautiful island with an intriguing history, stunning landscapes and some of Spain’s most exciting wines.

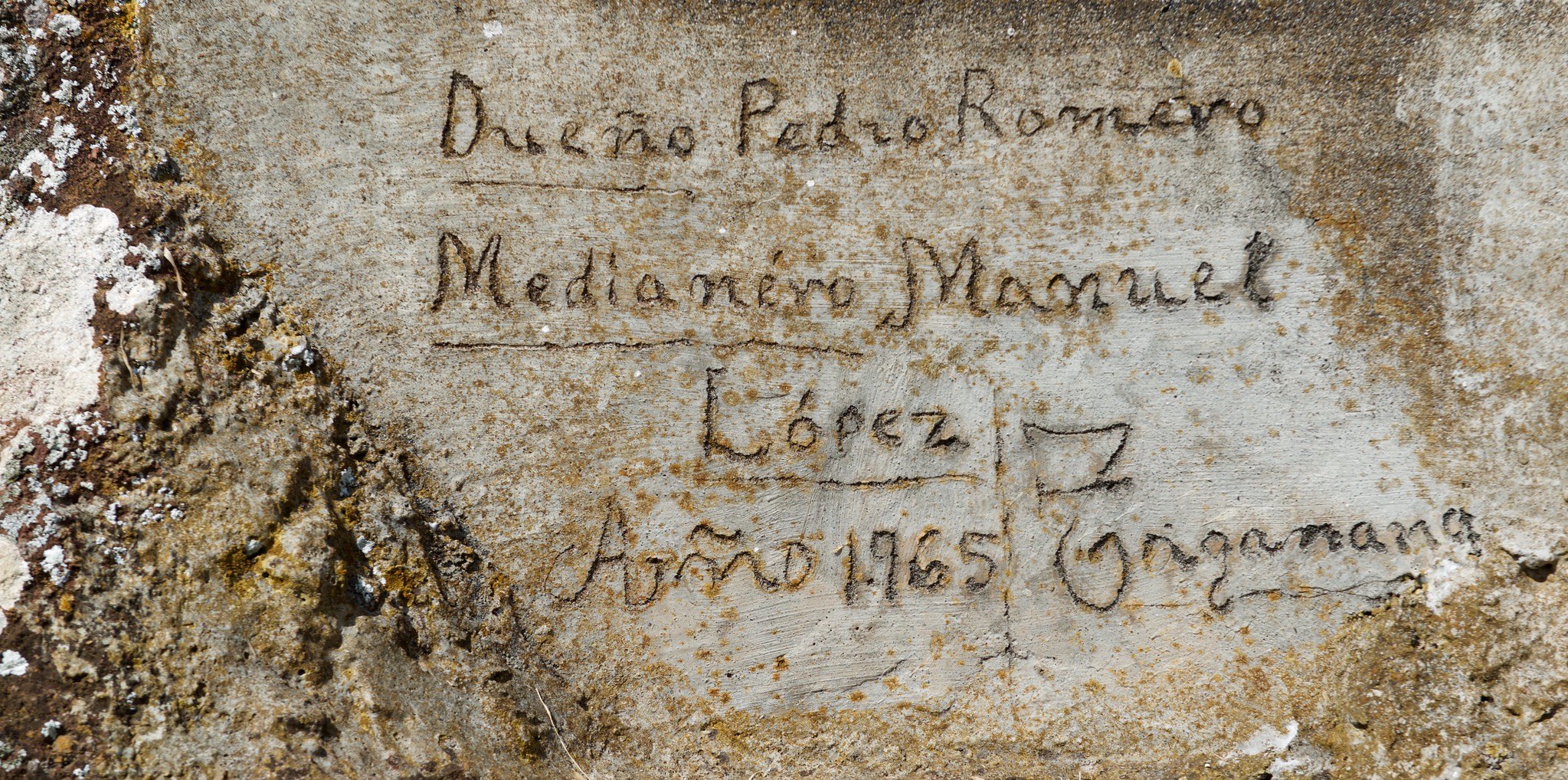

The combination of abundant sunshine hours, volcanic soils, water from the Teide, Spain’s highest mountain, and cooling trading winds, make this an ideal place to grow almost anything from bananas to potatoes. Grapes are no exception and have been planted here since the late 15thcentury. Because it has remained phylloxera free, 200-year-old vines are common.

In the 16th, 17thand 18thcenturies, the wine industry boomed, thanks to Tenerife’s strategic Atlantic position, which made it a vital point of call on long voyages to the Americas, the Cape and further afield. Wine was an essential cargo. As local historian Carlos Cólogan puts it: “Wine is pleasure today, but back then it was a necessity, as water went off after three weeks, whereas wine could last for up to three years. Without wine, you could die at sea.”

For various reasons, the local wine industry went into decline in the 1840s and continued on the same trajectory until the start of the 21stcentury. Now thanks to dynamic producers like Altos de Trevejos, Borja Pérez, Envínate, Los Loros, Tajinaste and Suertes del Marqués, Tenerife is recovering its past glories and even surpassing them.

The island’s area under vine of 3,020 hectares is nothing compared with what it was in its heyday, but some of its best sites are remarkable. Not everything Tenerife produces is great – roughly half of its wine is sold in bulk, often consumed in local cellar-door restaurants called “gauchinches” – yet its best wines are world class. The fact that the best vineyards now sell for as much as €120,000 per hectare – more than any other region in Spain – is proof of that.

What does Tenerife grow? The answer is a mix of Spanish, Portuguese and “local” grapes, as well as some that are as yet unidentified. Listán Blanco (Palomino) is the dominant white grape, while Listán Negro (probably a crossing of Listán Blanco and Negramoll, although some producers say otherwise) heads the list of reds. Together these two grapes, popular because they grow well all over the island, yield comparatively generously and are disease resistant, account for over 80% of production.

At their best, both make excellent wines in Tenerife’s rich range of terroirs, spread across five denominaciones de origen (Tacoronte-Acentejo and Valle de la Orotava on the wetter, cooler north coast, Abona and Valle de Güímar on the much drier, tourist-magnetic south side and Ycoden-Daute-Isora, which spans the two). There’s much more than the Listáns to Tenerife, however: the island is home to no fewer than 82 varieties, around 30 of which are in commercial production. Space prevents me from listing them all, but Albillo Criollo, Forastera Blanca, Marmajuelo and Vijariego Blanco (whites) and Baboso Negro, Tintilla and Vijariego Negro (reds) are all highly individual grapes.

What next for Tenerife wines? Funding from the European Union as well as the regional government, which has focused on identifying the best local grapes through the Enomac Project, is certainly helping, as is the increasing renown of a growing number of top producers. (We’re in the middle of a boom, with 110 bodegas making wine on the island.) The downsides are the low yields, the demands of growing vineyards in some of the steeper sites and the fact that there is no generic Tenerife appellation – wines have to be sold as one of the five DOs or under a catch-all Islas Canarias label, which can include grapes from any of the seven major islands.

More to the point, Tenerife wines are special, combining intensity with freshness and minerality. Juan Jesús Méndez of Viñatigo, another impressive producer, says that, “we’re the first New World wine area, even though we’re part of Europe” and he’s right in a sense. The Canary Islands are much closer to Morocco than they are to Spain. And yet the aromas and flavours you encounter here are unique, neither New World nor Old. Five centuries after Fernando de Castro planted the first vines in 1497, Tenerife remains a very special place.

Originally published in Harpers