And those who are

beautiful,

who can contain them?

Rainer Maria Rilke

Remember this! No

amount of Bacchic revelling can corrupt an honest women.

Euripides, The Bacchae

Last week a wine trade colleague shared – in dismay and anger – an article advising women on how to balance the personal and professional. It had been published and shared by We Are the City, an organisation supporting women working in London’s financial and tech industries.

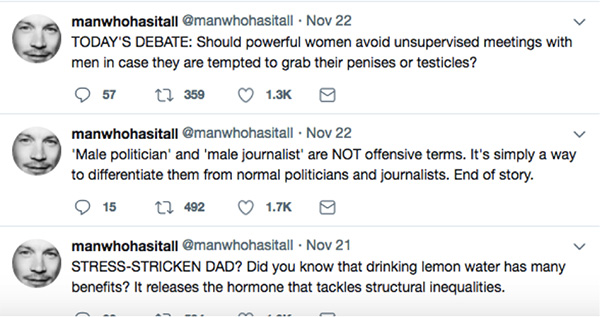

That article was facile and patronising. By way of dark solace, I directed my friend to @manwhohasitall a satirical twitter account (and now best-selling book) which ‘advises’ men on the issues normally reserved for women The account is sharply hilarious.

The argument expanded on my Facebook timeline. Those women-only ‘enclosures’ (as an acutely talented wine-writer friend put it) in networking, and on wine lists and wine tastings are ‘setting us back 30 years’. Another said that she had declined a networking group for women working in wine. Why rehash arguments that were won in the 70s? Surely there is nothing (and nobody) to prevent a woman’s professional success, so long as you are sufficiently resilient, committed and competent? The notion that a successful woman should be celebrated for having overcome the frailties of her sex is an anachronistic insult. A winemaker, Master of Wine, restaurateur, wine communicator, wine judge, CEO, or entrepreneur wants to be recognised for her achievements, not her gender.

And yet, in every other sector – of trade, industry and the arts – the importance of celebrating women as positive role models, and encouraging women to network and support each other, is undisputed. Diversity research and programs are in place at the highest levels of government and corporations. McKinsey have been researching gender disparity for more than ten years. The United Nations is promoting the #Heforshe initiative to engage men and women in eradicating structural inequality, including the eradication of “manels” – conference panels and speakers comprised entirely of men. Networking groups for women are there to help face the challenges of entering a business world with centuries of male-dominated culture behind it. All this attention is driven by both ethical and, as the McKinsey report makes clear, resource imperatives: gender-diverse boards outperform homogenous boards. Money talks.

Is the whole world patronising women with this affirmative action? Well, baby girls are born into disadvantage. A few numbers from that McKinsey report: 195 million fewer women than men are literate, and 190 fewer women than men have a bank account. Women comprise 50% of the global working age population, but contribute only 37% of global GDP. Women remain a minority in business leadership, holding 14.7% board-level positions globally.

I don’t blame anyone for not wanting to make a fuss about this. No woman does her job thinking “But I’m a lady.” And women who do speak out for gender parity – or even just exhibit symptoms of specialist expertism and independence of mind– risk ridicule (calm down dear!), personal insults, calls of man-hating, and even threats of violence. The uncomfortable fact is that if you are a woman in a position of authority, seniority and leadership in your field, you have beaten the odds. Yay, Jancis!

It is 89 years since women in the UK won the right to vote on equal terms with men. My great grandmother – whose house, cake and hands I still remember – was the first woman to vote in my family. The literary genius and free-thinker Mary Wollstonecroft was a hero of the Suffrage movement. Her book, Vindication of the Rights of Women, cried out in 1792 for women to have equal access to the world of ‘thinking, being and doing.’ She bashed it out in response to a move in 1791 by the French National Assembly to restrict female education to ‘domestic matters’. Egalité went only so far, according to the Prince of Talleyrand, author of the advisory report to the assembly, and owner of a certain Château Haut-Brion. Progress on gender parity is slow. British women could not open a bank account in their own name until 1975, 37 years after great granny got the right to vote alongside great grandad, and 5 years after I was born.

The wine trade cannot escape this global gender disparity, but we can choose to acknowledge and address it. Australian research indicates that wine degree courses are filled 50/50 by gender, but that only 10% of senior wine-making positions are filled by women. That’s a staggering loss of talent. A recent survey by the Women in Wine Awards of women working in Australia indicated that two-thirds of those surveyed had experienced sexism at work, and one-third of working mothers had experienced unfairness over maternity leave and pay.

That was the first survey of its kind in the global wine trade. But personal testimonies abound. At the heart of most is unconscious bias, although sexism and harassment are there too. A young woman moves from France to London to join a wine importer. Alone in a new city, she is taken out for lunch by the married, older, sales director who proposes an additional job as his mistress, offering career advancement and plenty of nice restaurants in return. The director of a PR agency answers the phone to a caller who asks to speak to the Director. “You are”, she says. “No, I mean the real Director”, is the reply. Young female PR executives are expected to put up with profanities and contempt from a noted male wine writer. (Fluffy girls deserve it don’t they? Not worthy of professional courtesy, never mind mentorship.) A wine critic is congratulated by a renowned winemaker on the referral from an eminent male MW: “You must be good. He doesn’t usually rate female palates.” The director of a 5th growth Bordeaux château tells how she was forbidden from entering wine cellars as a young woman, in case she was menstruating and thereby turned the wine sour. (I remember giggling at this superstition at University while reading Pliny, so it must be at least 2,000 years old. Still hanging on though.) A multiple award-winning English winemaker recalls an early employer “who suggested I’d make a good secretary for a wine merchant…that my looks and personality were my assets, not my brains, and I’d not go any further than that.” A colleague who raised the issue of ‘manels’ on a major wine industry conference program was met with bemusement, not concern. A few years ago, I politely declined an opportunity to film an interview with German Wine Queen candidates, explaining that I was uncomfortable with the fusing of a prize for professional expertise with a beauty contest. (There is no ‘German Wine King’.) I met with angry disbelief, despite an alternative interviewer taking my place with alacrity. Knowledge and beauty are both fine qualities, but young women working in wine need only to cultivate the former to bring value to any wine business, and I don’t want to be part of any message that says otherwise. (This is not the same as taking pride in appearance and dressing with style – that preoccupation is universal, and is about professional conventions and courtesy, and associations of diligence.)

Sarah Morphew Stephen was the first woman to enter the Institute of Masters of Wine in 1970, seventeen years after the exams were first held. In her 2013 address to the Gala Dinner held to celebrate the institute’s 60th anniversary, she told how her application to join the Symington winery in Portugal as a trainee was rejected with the statement that “there is no place in the wine trade for a woman”, and of the reluctance of the UK trade to accept “some kind of expert knowledge” from a woman.

Perhaps wine is one of those trades – such as tech, or finance, or construction – that is seen as ‘unnatural’ for women? From Euripides’ compellingly wild Maenads to the Daily Mail’s “Ladettes’, there is an ancient but vivid distrust of, even disgust for, women consuming alcohol on their own terms. The potential disinhibition is unfeminine, and dangerous. And there’s an idea that it required manly power to master alcohol. A decent fellow will keep the little lady on the right track and order her a dainty half. But a cad will get her drunk. We each need to be mindful of the joys and dangers of alcohol, but there is nothing that makes women less capable of personal responsibility in this than men. We need to talk with all our young people, whatever their gender, about the importance of responsible consumption. (But that’s another rant.)

Perhaps it is the old link between traditional wine estates, which tend to be the preserve of the rich and established, and a certain conservatism. Three centuries ago, Talleyrand sought to contain women as homogenously domestic beings, their scope narrowed and defined by their gender. It is strange to me that wine world, so in love with the notion of the beauty of nuance, and the expression of diverse and intersecting influences in wine, is not more passionate about fighting for this infinite nuance and potential in its people.