I’m not sure if Peter Lehmann and Tim Hamilton Russell ever met, but I like to think they would have got on, despite their very different personalities. One was a slightly gruff, chain-smoking winemaker who never went to university, the other an urbane, Oxford-educated advertising executive. What they had in common – and would, I hope, have established a bond between them – was a love of wine and an ability to take risks, flouting rules if necessary.

Now we shall never know. Lehmann died on June 28th, followed less than a month later by Hamilton Russell on July 17; they were 82 and 79, respectively. Both made huge and lasting contributions to their national wine industries. Lehmann, dubbed the “Baron of the Barossa”, was one of the key Aussie winemaking personalities of the last 50 years; Hamilton Russell was the man who established Hermanus (now known as the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley) as a cool climate region against a good deal of official opposition.

Lehmann was as Australian as vegemite. A fifth-generation winemaker of German descent, he was born in Angaston and never seemed to feel at ease outside the Barossa. He was happiest sitting on his beloved weighbridge, chatting to growers, young and old, as they delivered their grapes and teasing the occasional passing journalist. When he won the International Wine Challenge’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010, I asked him how he felt to be honoured with a standing ovation. “Bloody long way to come for a gong, mate,” he said.

Over the years, Lehmann worked for Yalumba and Saltram, both great Barossa wineries, before he set up his own eponymous operation in 1980. Two years before that, he had earned the gratitude of Barossa growers when he refused, as Saltram’s chief winemaker, to renege on a deal to buy their grapes. His principles were to stand him in good stead when he left. The bond between Lehmann and his 140 growers was plain to see. They appreciated his loyalty and deep love of the Barossa and rewarded him with fine fruit.

Lehmann and his long-term winemaker, Andrew Wigan, made some great wines together (they were best known for their Stonewell Shiraz, but the whites, particularly the Semillon and the Riesling, were often superb, too). If anything, the range improved after the Hess Collection acquired the business in 2003. It was significant that the Lehmanns retained some of the shares and were allowed to continue pretty much as before. Their wines enjoyed popular success as well as critical plaudits.

The styles of wine that Tim Hamilton Russell decided to make in South Africa were very different from those of the Barossa. He bought a farm in Hermanus in 1975, convinced that the area, better known for whale watching than grapes at the time, was well suited to growing refined Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. His conviction was shared by very few. Indeed, he had to battle with the KWV, whose notorious quota system effectively prevented people from planting vines in new wine regions. A second fight was to obtain decent, virus-free clones, rather than the high-yielding material favoured by the KWV.

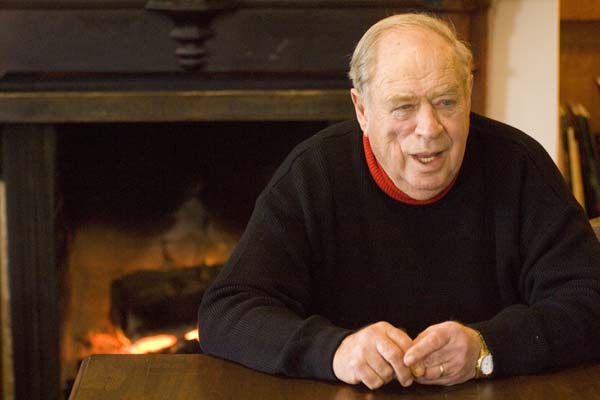

Hamilton Russell persevered. His easy charm and advertising background as chairman of J Walter Thomson were both assets when it came to enlisting the support of journalists. But Hamilton Russell had integrity, too. He was among the first South African wine producers to campaign for better treatment of vineyard workers at a time when apartheid was still the Cape’s governing ideology.

The man was a pioneer in all three respects. The Hemel-en-Aarde Valley is now recognised as one of the best places in South Africa to grow Chardonnay and Pinot Noir; Hamilton Russell’s example inspired other wineries, such as Bouchard Finlayson, Ataraxia, Creation, Newton Johnson and Crystallum among others. Plant material is better now than it has ever been, although quarantine restrictions are still stringent. And conditions on wine farms, while far from perfect, have improved immeasurably since the early 1980s.

Hamilton Russell played his part in challenging the government and its agents. But his lasting contribution to the Cape wine scene was much more important. As well as creating a new wine region, he encouraged many other producers to trust their hunches and go it alone. The wineries that have emerged since 1994 – including many of the leading names of today – owe a debt of gratitude to him. It is not an exaggeration to call him “the father of the modern South African industry”, as the local wine writer, Michael Fridjhon did recently.

Hamilton Russell and Lehmann have been succeeded by their sons, Anthony and Doug. Both are chips of the old block, or possibly samples from the same barrel. Doug shares his dad’s passion for the Barossa as well as his ribald sense of humour; Anthony is cool, debonair and intelligent. Both wineries are in good hands. And that, in the end, is what matters. The work of these two remarkable, if contrasting men, continues.

Originally published in Off Licence News