Edmund Penning-Rowsell’s vast The Wines of Bordeaux (1969) is more textbook than billet-doux, though you won’t come away from it knowing how to make wine or grow grapes any better than you did before picking it up (those modules came two years later with the publication of Émile Peynaud’s chiding Connaissance Et Travail Du Vin.) Neither do the subtle encryptions of terroir – wine writers’ most recently cut master-key – get a look in. As with Jancis Robinson MW’s Oxford Companion to Wine, EP-R’s affection for his subject has to be inferred from the veil and volume of facts. The book is all dates and details: changes of ownership, wars, genealogies, and patterns of trade. The slow flow of words and history eventually winds to a halt in columns cataloguing opening prices back to 1831. Over the course of its 624 pages, I learnt how Bordeaux’s maritime past is as integral to claret’s character as salt is to the estuarine air. In its own drawn-out way, The Wines of Bordeaux solves the puzzle as to how a climatically compromised region on the wet edge of Europe became the hegemon of global production.

Though he was credited with owning one of the country’s finest private wine collections – more Pétrus 1961 than the Château itself, according to Jean-Pierre Moueix – Penning-Rowsell was a life-long socialist. Another seeming contradiction, except left wing views were commonplace among tweedy types who’d lived through Europe’s slaughter years. Having sympathies for Keynes and Polyani didn’t mark you out as dissident.

The gentlemanly response to capitalist alienation wasn’t bloodletting but redistribution and the promotion of workplace dignity. Industrialisation robbed employment of its capacity to bring social and productive pleasure to people’s lives (Marx had a soft-spot for feudalism). William Morris’ cascading vision of a society based upon artisan entrepreneurship (EP-R founded The William Morris Society) looked a lot like viniculture, particularly when viewed in reverse, from bottle back to vigneron. Rather than revolution, the Arts and Crafts movement would, like electricity, conduct into all areas of society, revivifying repressed feelings of self-worth and connectedness as it spread.

The idea that wine might be a partial antidote to the very inequalities for which it had become a symbol – abandoning brash associations for a redemptive, utilitarian calling – is still with us, even if the terms and targets have changed. Terroir has taken on the responsibility for benign transmission, in part because EPR’s preferred vectors of Latour and Palmer 1961 (£17 and £9 per bottle in real terms) caved-in to the very market pressures he’d hoped they’d resist. Small domain, low intervention wine, so the present line goes, is open to a transference of site specific traits from which industrial production is, by its approach, barred. Not only are these place-driven wines better than heavily processed competitors, but their inherent expressivity has the potential to roll back and reclaim territory commandeered by, and subjected to, decades of mismanagement. The roster of sinners now includes the ragtag emissaries of capital – marketers, shareholders, banks, governments, agro-chemists – but also, depending upon which side of the fence you fall, natural and biodynamic makers and consumers.

Putting factionalism aside, such widely dispersed aesthetic encounters come with the hefty assumption that there’s always gold waiting at the end of the rainbow, something worthy of revelation, and that the qualities of Le Pin and Gevrey-Chambertin are less like exceptions and more like the rule. One way of getting beyond this uncertainty is to elevate diversity over and above evaluative hierarchies, identifying oneself with new heroes, methods and varieties in preference to the established order of growers and regions: Pineau d’Aunis, Lapierre, Aligoté. Developing the right kind of persuasive wine experiences then becomes a matter of installing righteous farmers and burying a few dozen cow horns on the autumn equinox.

With good cause, marketers retaliate by telling us that E-PR’s longed-for utopia reads a lot like their job descriptions. Brands have accelerated distribution, broadening the category’s appeal. It is thanks to them that the redistributive project didn’t flop when we realised there wasn’t enough Haut-Brion to satisfy South West London, let alone The Empire. Fortunately, Casillero del Diablo and Nottage Hill flooded in, filling the void in the master plan.

Focusing on Bordeaux and Burgundy meant the English wine trade’s resident Left Bank failed to spot the bigger picture as it materialised before them, in colour. The revolution wasn’t on television because the revolution was television. Improvements in post war living standards are measurable in brand ownership and holidays, not Pétrus. With machines and tech taking over the burden of alienation, the left’s longed-for double movement of connectivity and collectivity was realised as saturated leisure time. All those principled tie-ins with Antiquity, the Cistercians and God’s Earth were destined to become props, merely there to aggrandise personal journeys. Drinking wine doesn’t, as E-PR once hoped, awaken us to a universal humanity, any more than Humbert Humbert’s prose saves him from being a monster. Kim Jong-un’s Romanée-Conti habit has, as far as I can tell, only made him fatter.

If wine is versatile, it is because it’s grown up with us for company; at our sides through the good, sad and weird bits. Depending upon how much Hegel you’ve stomached, alcoholic disinhibition is just as capable of facilitating spirited discussion as it is of sparking a mood of crass togetherness.

Take the two buddies in Sideways, Miles and Jack. Miles is a romantic, and believes their relationship needs rebooting with the kind of platonic intimacy that wine appreciation stirs between friends. Together they take a road trip along the Santa Ynez Valley, where Jack, to the despair of Miles, directs all his energy and any available transcendent wine properties towards getting laid.

The most memorable scene in the movie finds Miles on his own in a burger joint draining the punt of Cheval Blanc 1961 into a Styrofoam cup . Beneath the humour lurks a contradiction: free market ideology rewards the individual. Accordingly, the highest pleasures are subjective and private, and therefore at odds with wine’s established culture of sharing.

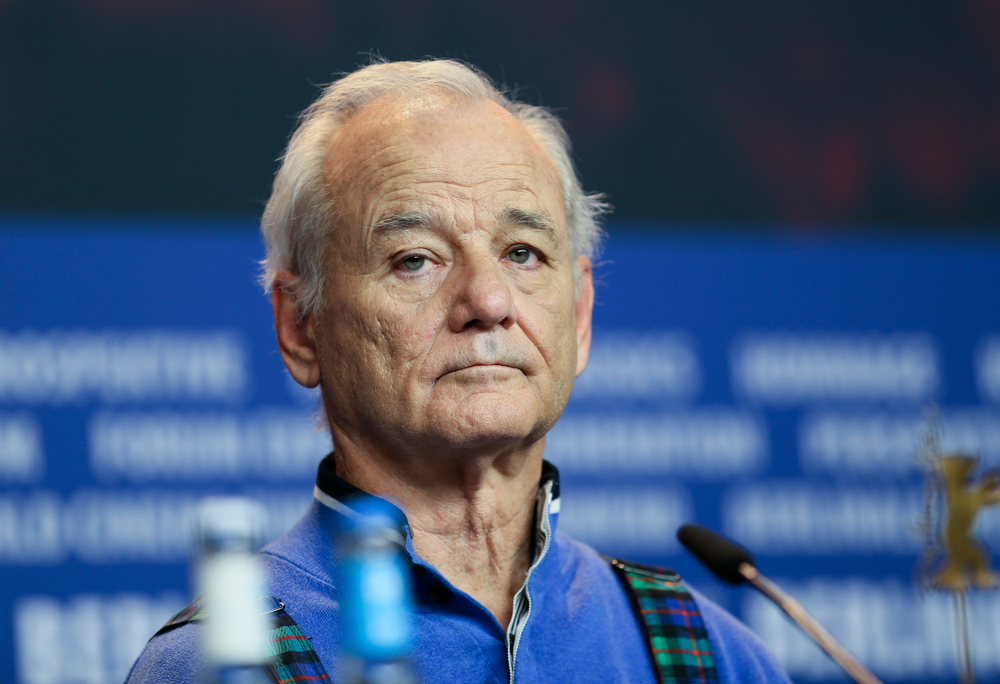

Watching Miles again made me think of Lost in Translation, only with DRC newbie brand ambassador David Beckham living out the jetlagged Bill Murray role in glutinous real time. Golden Balls can’t emulate Murray’s’ sardonic turn – few can – but he does have ink to spare.

Tattooed fingers wrap around a tumbler of AC-chilled La Tâche 2017. He stares beyond his penthouse suite over another identikit Orient cityscape: miserable, bored, alone.

I’ve heard similar tales of cultural misappropriation featuring wealthy young bankers (presumably doctors’ income levels now grant them impunity ) who only register for the basic WSET course after they’ve acquired a cache of top châteaux. The late John Forrester notes that wealthy collectors share ‘the desire to free a space in which money, while not excluded, does not rule.’ Subjectivity can only leverage the pleasure principle so far. In the late 1990s, I sold the cellar of a derivatives trader who was too impatient to wait for his wine to mature, and wasn’t ‘prepared to waste good bottles on guests anyhow!’

None of these stories would comfort EP-R. One only has to look at the fine art market to see what a pushover rarefied aesthetic experience is for investment capture. Collecting Koons is a quest for immortality in the same way that erecting statues is. You’re set on securing your legacy, hoping to be commemorated for all the right reasons, when someone belatedly points out all the other shit that happened in your name. Like planting a cool, marginal vineyard site with the proceeds from decades of oil extraction.

Aesthetic encounters aren’t a great leveller, unless you genuinely believe packaging passes for high art. Yet there is still something salutary about City traders enrolling for WSET Level 1. As Peter Sloterdijk has pointed out: in a present structured by algorithms, forecasts and programmers, technology is forced to slow down so that we, the lumbering consumers and workers, can keep up.

Wine may not be redemptive in the way that E-PR wished, but perhaps it can reintroduce the virtue of patience into increasingly impatient ways of living.